This article originally appeared in Issue 40:2 (Nov/Dec 2016) of Fanfare Magazine.

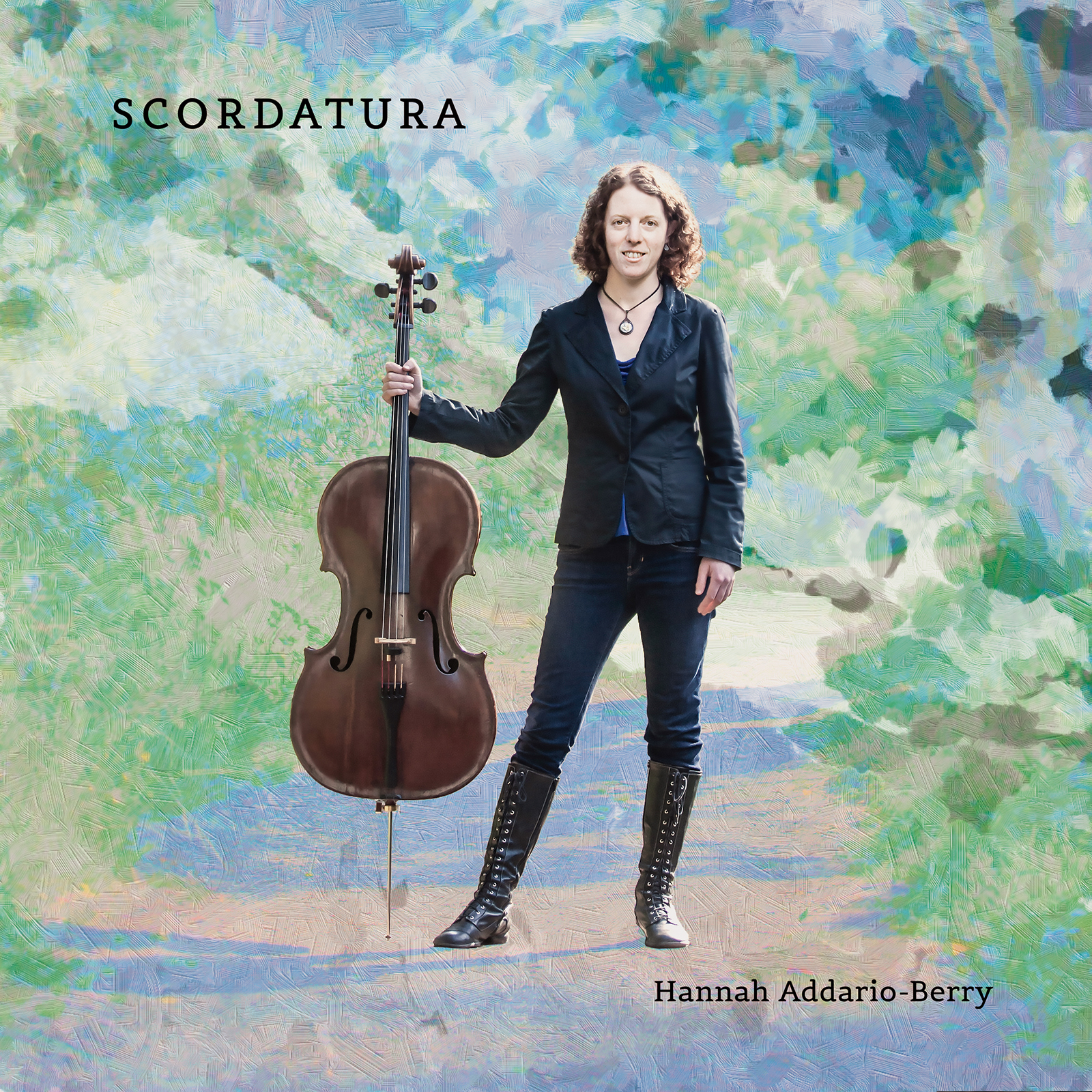

SCORDATURA • Hannah Addario-Berry (vc) • AEROCADE 004 (77:09)

KODÁLY Sonata for Solo Cello, op. 8. B. MILLER Miniatures, Book 3: Koans. A. ROSE Lands End. E. CLARK Ekpyrotic: Layerings IV. JUSTEN Sonaquifer. COONS Myth’s Daughter. LIU Calor

Kodály’s Sonata for Solo Cello dates from 1915. An early twentieth century answer to Bach’s music for unaccompanied cello, it shows the influences of Claude Debussy and Béla Bartók had on him. This sonata also shows the way he used the native Hungarian folk music that he and Bartók loved to work into their pieces. Over a hundred years later on this recording, the solo cello sonata becomes a base that undergirds the varied styles employed by twenty-first century composers of music for the solo cello. The recording is called Scordatura because all of the featured works use the same altered tuning required by Kodály in his solo cello sonata. Kodály’s music requires the cellist to cover the instrument’s entire range from the highest delicate tones to the strongest bass notes, so this fine rendition of his solo cello sonata gives the listener an idea of Hannah Addario-Berry’s superb virtuosity. Janos Starker, who actually played the Kodaly sonata for its composer, recorded it for Delos in 1992. That is the most definitive recording but, because of technological improvements over the years, not necessarily the easiest one to enjoy. I would suggest owning the Starker for study and the Addario-Berry for simple enjoyment.

Hannah Addario-Berry commissioned each of the six widely varying new works heard on this disc. Composer Brent Miller, managing director of The Center for New Music in San Francisco, describes “koans” in Book 3 of his Miniatures. Koans are stories, dialogues, questions, or statements used in Zen practice to test students’ progress. Miller scores the piece for cello, voice and dice. The text is from The Gateless Gate, a collection of Zen koans and commentary compiled by Chinese Zen master Wumen Huikai.

Alisa Rose’s Lands End is a musical hike along Northern California’s Lands End Trail that leaves city and suburbs for the untamed nature of a dirt trail that skirts the Pacific Ocean. Rose’s rhythmic fiddling has an old time feeling because she uses open strings as drones and drums. Violinist Eric Kenneth Malcolm Clark specializes in new and experimental music. His Ekpyrotic Layerings IV for Solo Cello and Tape requires the cellist not only to change the tuning of the strings but also to place pins on them that give them bell-like tones. The result is a fascinating romp through inventive composition. Gloria Justen’s Sonaquifer makes my mind see a dance of celebration when dusty travelers find a source of clean drinking water for humans and animals in the middle of California’s broiling desert.

If you remember a parent reading a fairy tale to you, Myth’s Daughter will whisper sweet sonorities in your welcoming ears. Step into the musical garden and it will hold you in its thrall.

Addario-Berry’s final work for this performance is Jerry Liu’s Calor, which is Spanish for heat. Here the cellist mesmerizes the listener with hot rhythms and shows us the beauty of an unrestrained sun. The pristine sound on this Aerocade recording allows cello, voice and percussive sounds to be heard as clearly as if the listener was in a well built recital hall. I enjoyed the variety of compositions Addario-Berry commissioned and hope she will continue to help talented composers get their cello music in front of the public. Maria Nockin